The Guide to

SaaS Metrics

The Guide to

SaaS Metrics

Table of Contents

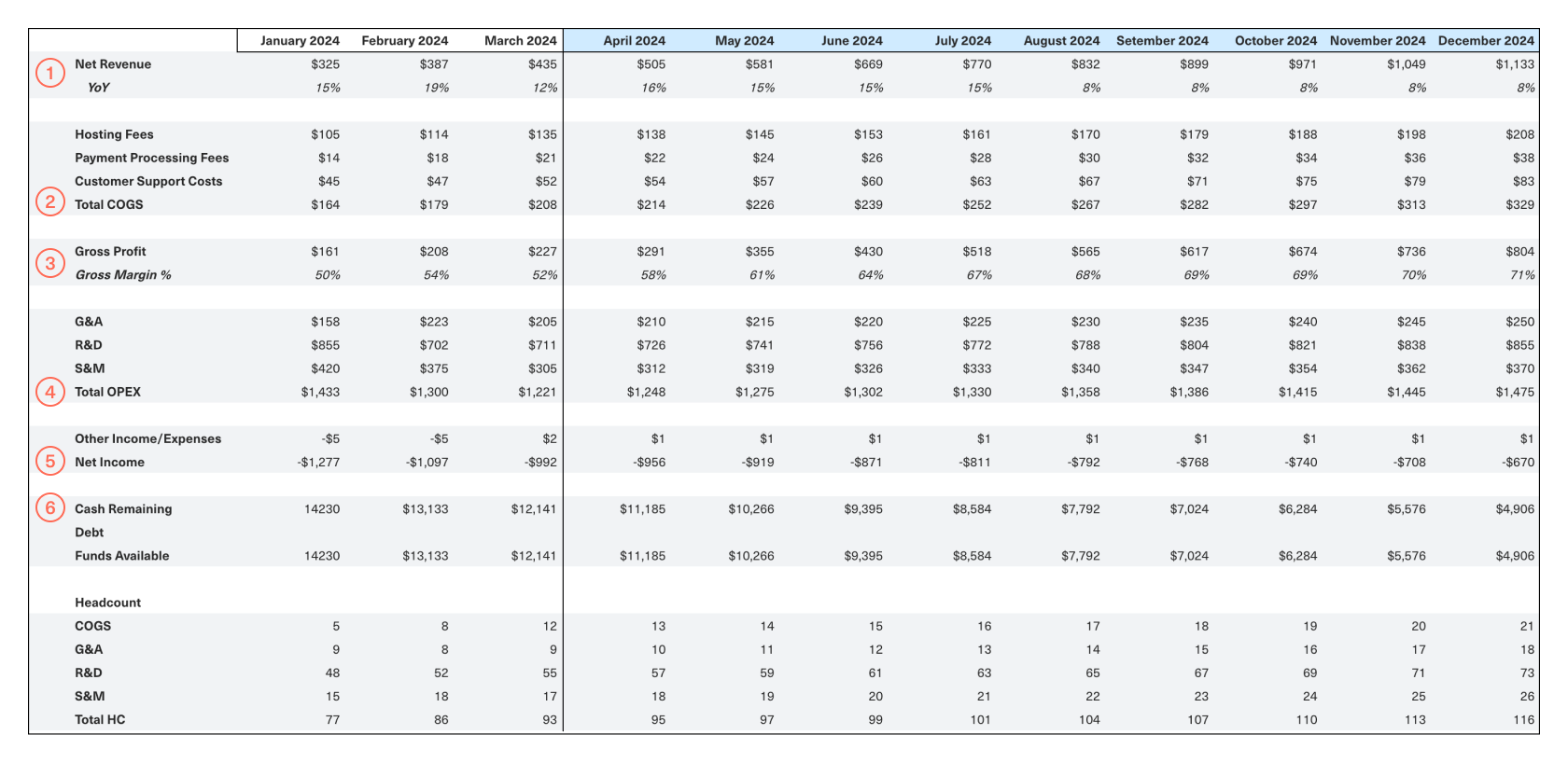

Operating Model (P&L)

The purpose of your Operating Model – and in particular the P&L – is to show not only the profitability but also the liquidity of your business. It provides a view into the efficiency of your business operation and the impact this has on the cash reserves you have on hand to keep that operation running.

Reading from top to bottom:

- Start with Net Revenue

- Subtract the costs of servicing that revenue (Cost of Goods Sold, AKA COGS)

- Arrive at Gross Profit (and Gross Profit Margin)

- Subtract your overhead costs (Operating Expenses, AKA OpEx)

- Arrive at Net Income

- Finally, use Net Income to forecast your Cash Balance

Here’s a breakdown of every major line item you’ll find in your P&L.

Revenue

While recurring revenue (or ARR) is at the core of the SaaS business model, Revenue as accounted for in your Operating Model encompasses both recurring and non-recurring revenue. This includes things like revenue from one-time implementation services, capital injections, one-time sales of assets, and interest income.

Another distinction between ARR and revenue, as reflected in your Operating Model, is timing. Depending on whether you’ve used accrual or cash-based accounting, revenue that is included in your ARR may or may not be immediately reported on your P&L.

Gross Profit and COGS

You can calculate Gross Profit by subtracting the Cost of Goods Sold (COGS) from Revenue:

From which you can infer your Gross Margin:

COGS includes all costs that are directly related to delivering your product or service to customers. Said differently, it’s the cost required to service your ARR, encompassing everything you would continue to spend to serve customers even if you were to stop all acquisition activity tomorrow. These include line items like server hosting fees, payment processing fees, data security, and customer support.

As a result, your Gross Proft provides a view into the efficiency by which you can convert the costs of servicing your customers into revenue. This is the profitability of your core business operation before considering the impact of overhead costs.

Operating Expenses and Net Income

Operating Expenses (or OpEx) are the costs required to keep the lights on for your business. There are three primary buckets of OpEx for a typical SaaS business:

- Research & Development (R&D): Costs associated with developing your product or services, including salaries for your product and engineering teams, as well as tools needed for development, testing and design.

- Sales & Marketing (S&M): Costs related to selling and promoting your company's products or services, including advertising spend, salaries and commissions for your sales team, and CRM or marketing automation platforms. These directly inform your Customer Acquisition Cost (CAC).

- General & Administrative (G&A): Day-to-day operational costs that are not directly tied to product or go-to-market, such as salaries for executive leadership, administrative staff, people operations, finance and analytics teams, and legal fees.

Breaking out your OpEx into these buckets allows you (and your investors) to determine how investment in each area of the business correlates with overall business growth and efficiency.

After subtracting OpEx from Gross Profit, you arrive at Net Income:

This is the fullest accounting of the profitability of your entire business after considering both COGS (the cost of servicing your revenue) and Operating Expenses (overhead).

Cash Flow

Using Net Income as a base, you can then calculate your Cash Flow to understand how much cash your business is actually generating and using. This represents the capital reserves that will allow you to plan for future investments, manage debts, and ensure operational stability.

Your ability to bridge directly from Net Income to Cash depends on whether you’ve followed a cash-based or accrual accounting method. If you’ve used cash-based accounting, Net Income is effectively the same as Cash Flow because all transactions recorded in your P&L are based on actual cash inflows and outflows.

If you’ve used accrual accounting, you’ll need to adjust Net Income to bridge to Cash. This is done by subtracting gains or adding losses that are included in Net Income but that don’t involve the exchange of actual cash. For example:

- Adjust for non-cash expenses like depreciation and amoritzation.

- Account for changes in working capital, like decreases or increases in your accounts receivable and accounts payable.

- Adjust for the cash impact of other items, like interest income and tax payments.

Accrual vs. Cash Accounting

There are two primary methods of accounting for your revenue and costs: Accrual Accounting and Cash Accounting.

The difference between them boils down to the time that elapses between when cash changes hands and when services are actually delivered. In cash accounting, revenue is recognized when your business receives cash. In accrual accounting, revenue is spread out (or amortized) over the period during which you deliver your service to your customer.

For a simple business like a flower shop, your cash inflows and outflows will generally happen at the same time that your business delivers or receives services. Each month, you’ll know how much your customers paid for their flowers (revenue), how much you paid to buy and maintain those flowers (COGS), and how much you paid for salaries and rent (OpEx). At the end of the month you’ll net out all those buckets of revenue and cost to arrive at your Net Profit, which will directly inform your available Cash.

For most SaaS businesses, the timing by which revenue is recognized (your revenue schedule) is more complex. Take the example of a SaaS company that signs a customer to a $12,000 annual contract. While the business receives that amount upfront from the customer, under accrual accounting, the $12,000 contract value would need to be amortized over the 12-month term of the contract (otherwise known as the benefit term) at a rate of $1,000 per month. Similarly, expenses such as a $12,000 AWS contract paid upfront would be recognized at a rate of $1,000 per month over 12 months.

At scale, this can get pretty convoluted–which is why large companies have entire finance teams to handle revenue and expense recognition. Our recommendation for most early-stage startups is to simply account for revenue and expenses on a cash basis. That means that you’ll account for $12,000 in COGS the month you sign your Amazon AWS contract and $12,000 in revenue the month your customer signs that annual contract with you.

Why? Because the bottom line for any early stage startup is cash. Most startups don’t have the luxury of falling back on massive capital reserves, so cash flow is their lifeblood. Without it, they won’t be able to pay employees, keep their servers running, or navigate volatile periods of growth. That’s why it’s important that you have visibility into the cash you have on hand at any given point in time–and with cash-based accounting, you can easily bridge Net Income directly to Cash.

If your accounting is on an accrual basis, that’s okay too (and will provide a more nuanced picture of your finances as you scale). Just keep in mind that not all expenses and revenue will show up in your P&L immediately and that you’ll need to adjust your Net Income to arrive at your Cash.